Building a strong company culture takes a wide-angle lens and an eagle’s eye for detail. It’s a never-ending mission that starts at every employee’s job interview and lasts through their tenure at the company—which, if the culture is strong enough, might see them rise from entry-level to industry leader. Perhaps most importantly, it requires simultaneous trust in best practices and a willingness to embrace new ideas: one foot in the past, the other in the future.

So argued the guests on a recent episode of The Community, SLIF’s webcast series. Titled “Does Culture Really Matter?” (spoiler alert: yes!), the discussion featured Rustin Becker, CEO of ERDMAN, a real estate development, architecture, engineering, and construction firm; Tana Gall, President of Merrill Gardens; Tod Petty, Vice Chairman of Lloyd Jones Senior Living; and Charles Turner, CEO of KARE, a platform that allows caregivers to manage their own schedules and earn extra income. Throughout their conversation, they discussed how to build the culture you want, how to measure it, and whether it really matters to frontline caregivers.

What is Culture?

“It’s everything from head to toe, the minute that somebody interviews with us—making sure that they’re aware of what the culture is to work at a Merrill Gardens community—to what their onboarding is like,” said Gall, who started at Merrill Gardens as a public relations manager and now serves as its President. “And then the ongoing check-ins with the employee when they start working with us, and then we’re just making sure we’re always living it. And if we’re not, we want people to call us out on it.”

“It starts really where we interview,” agreed Becker, explaining how ERDMAN’s process focuses less on technical skills than behavioral ones, like problem-solving and conflict-resolution. This approach naturally promotes teamwork, he argued, which over time fosters a robust culture. “What we need is individuals to model a way that they approach that conflict around what the problem is and not what the individual is,” he said. “If we can model that, or get teams to model that behavior, the bonds that they have with each other will increase.’

Petty argued that a strong culture is impossible without a strong vision, one that attracts employees who share it. “It actually gets back to having the right people in the right seat. How do you attract people into your communities that are gonna be there long-term to help create this culture?” he asked. “I wanna find a way that I can attract people that… can grow and mature and become leaders in our industry.” But it’s not just about attracting them—it’s also about nurturing them, giving them the tools they need to succeed in the long term. “If they're not celebrated, they're not reinforced, they're not edified, they're not recognized in their communities, they can get burned out and they can leave you,” he said. “So you have to find ways to celebrate that community at the local level.”

Petty stressed the need to balance innovation in culture-building with a respect for the fundamentals, warning that you can’t successfully pursue either at the other’s expense. “I know folks that are like, 'Hey, we're just gonna be about tried and true operations, we're gonna be good operators,' and they resist the innovation,” he said. “And so it becomes very plain, very vanilla, with no magic within their businesses. But I've also seen people throw out tried and true operations and say, 'Yeah, we're just gonna be so innovative. If the glass is looking good, we're gonna break it and we're gonna rebuild it and we're gonna be cool and hip and just have innovation.’ And then we lose out on tried and true operations that we need to have a good foundation in our communities.”`

Measuring Culture

Building culture is only half the job: the other half is measuring and maintaining it, making adjustments as necessary. Gall described this process as one of listening and learning. She makes sure Merrill Gardens delivers on its cultural promises by keeping up on the company’s Glassdoor and Google reviews, paying close attention to her peers’ and business partners’ input, and regularly checking in with employees at Merrill Gardens’ communities—especially its general managers, whom she meets with via Zoom every Monday. “The general managers are a real key component to culture,” she said. “To me, they're the ones setting the tone in their communities. And I think a lot of people would say when you walk into a community, you can tell the personality of a general manager [or] executive director by how the community feels.”

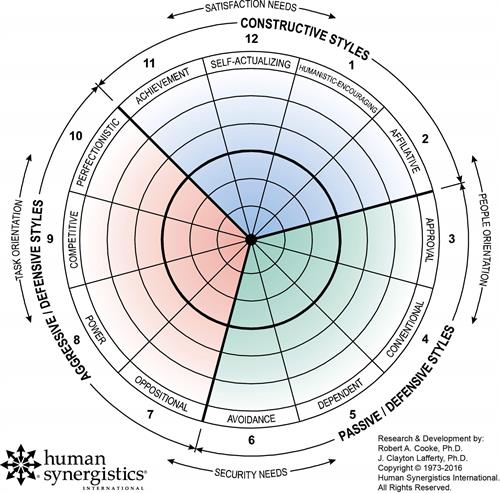

The Human Synergistics Circumplex Model

ERDMAN, meanwhile, takes a distinctly methodological approach to measuring culture. The company partners with Chicago-based consulting firm Human Synergistics, using its Circumplex model to evaluate culture and performance through behavioral styles. The model breaks down individual, group, and organizational impact into 12 behavioral styles that fit into three clusters: constructive, aggressive/defensive, and passive/defensive. As Becker explained, ERDMAN used this model to track the evolution of its leadership team over the last several years, ensuring that the changes it’s made have resulted in more constructive impacts that trickle down to the rest of the organization.

“A Matter of Individual Respect”

While the discussion centered on the company culture of a whole organization, one guest took care to emphasize the perspective of frontline caregivers. “When you get down to the frontline worker level, that culture becomes much more individualistic,” said Turner. “Culture, to them, is a matter of individual respect, not ‘What are the values of this company?’ Those values tend to be a lot more abstract to a frontline worker. Because for them, their culture and their reinforcement is—how do I give care? Are you respecting me for giving care?”

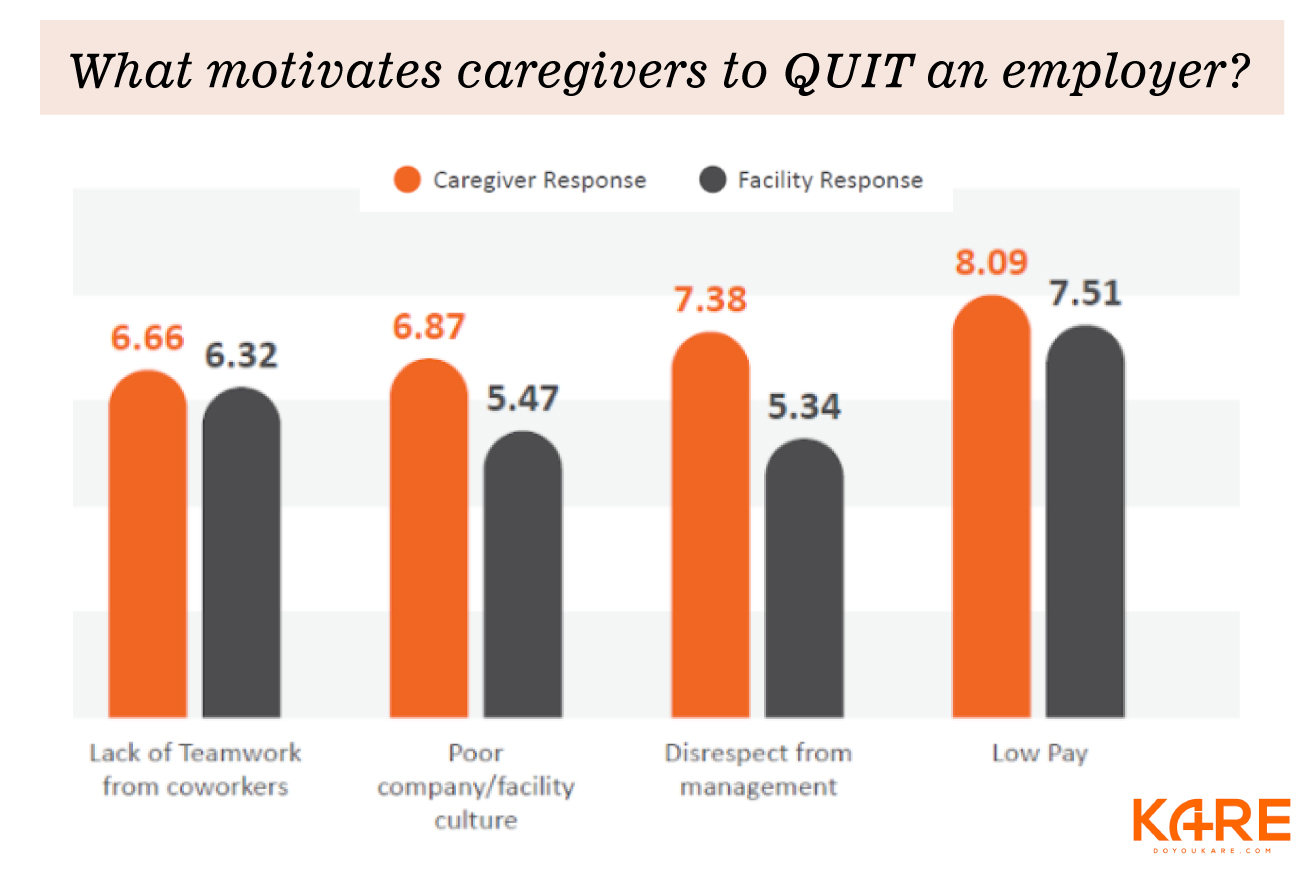

As Turner explained, KARE’s research into workplace concerns at the front line found that pay tends to be a higher priority than cultural factors. In a poll of 227 caregivers about what motivates them to quit an employer, “low pay” was the highest-ranking response; the next three, with roughly the same rankings, were “disrespect from management,” “poor company/facility culture,” and “lack of teamwork from coworkers.” For Turner, this suggests that caregivers see teamwork from coworkers and respect from management as inextricably bound up in a community’s culture.

But even this idea of culture may not be more important to frontline workers than pay. Asked whether they’d accept lower compensation for a company with a great culture, the respondents to KARE’s survey were not enthusiastic. “The caregivers were like, “Yeah, no, we're not taking less pay,’” Turner said. (“People do regret leaving for more money,” Petty pushed back, citing a recent Wall Street Journal survey of 1,000 workers who left their jobs for higher-paying roles. “I think culture has to be in play because money is a temporary motivator.”)

Treat Frontline Associates as Equals

Still, the panelists agreed that a strong culture is impossible if workers are not treated with respect. KARE’s research handily clarifies what exactly that means for frontline caregivers: taking their ideas seriously, not micromanaging them, and treating them as equals. “If you’re gonna work on culture, work on how to get your EDs to treat your frontline associates as an equal,” Turner said, echoing Gall’s observation that a community’s Executive Directors and top managers are the key to its culture. “That’s the first quick win I would attack.”

Becker offered similar advice, suggesting that the customer should be central to any conversation about culture. “Ultimately what that resident experience is, is what the culture of the organization is,” he said. By building a strong, attractive culture, communities can differentiate themselves in a highly competitive market, both as a provider and as an employer. “It is very effective in terms of recruitment,” Becker concluded. “We’ve been able to recruit very successfully throughout the pandemic.”

Posted by

SLIF heads to Carlsbad!

The One of a Kind Retreat for Senior Housing Leaders.

May 31 - June 2, 2026 | Carlsbad, CA

Learn More

Comments