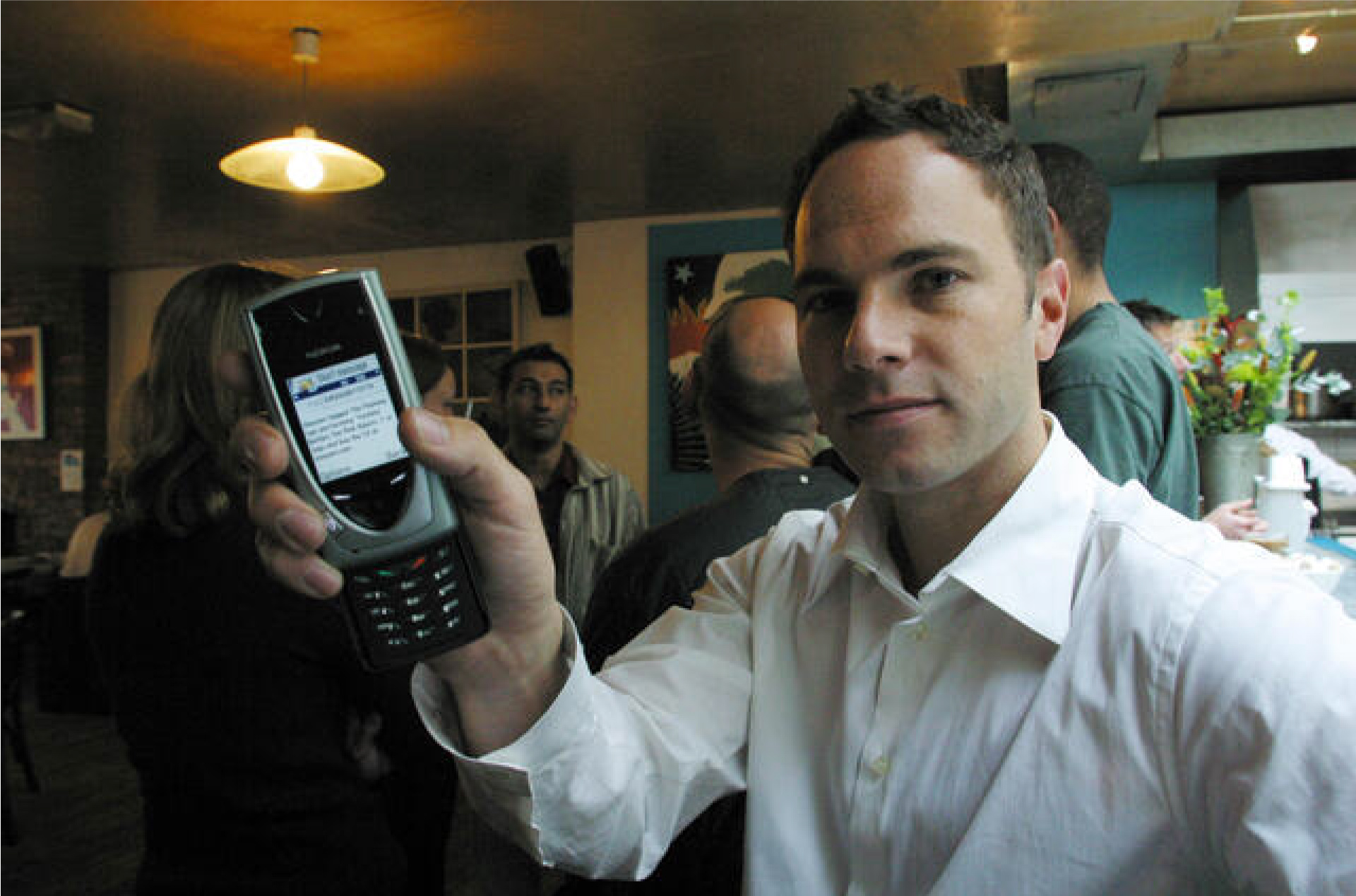

Before it was an app you could use to identify music, Shazam was a number you called from a pre-smartphone mobile device. (Remember those?) Before it was a number you called, it was a crazy idea in the mind of Shazam’s founder, Chris Barton – who came up with it more than seven years before the invention of the iPhone.

Today, Shazam has been downloaded more than two billion times. Purchased by Apple in 2018, it routinely receives 8 million monthly downloads without spending a dime on marketing. Once-in-a-lifetime innovations like this might seem like the domain of Silicon Valley wizards, but Barton believes anyone can come up with truly game-changing ideas. All it takes is a novel insight, a little obsessiveness, a frictionless experience, and an emotional connection to the idea.

In a recent presentation at the Senior Living Innovation Forum, Barton explained how this methodology turned Shazam from an impossible idea into reality, outlining what senior living providers can learn from his approach.

Thinking from First Principles

Great ideas don’t emerge from thin air – not exactly. As Barton explained, many of history’s greatest innovators, like Leonardo da Vinci and Steve Jobs, developed their breakthroughs by thinking from first principles: that is, by interrogating the status quo until they arrived at the fundamental rules beneath it. “You don't start from the familiar; you actually question the familiar, you question all the assumptions that we're making,” Barton said. “As you question those assumptions, you're able to break down what's an assumption and what is a basic truth. And once you have those basic truths, that's where you begin.”

The more common, but less creatively fruitful way of thinking is analogical: building on the familiar. This is the approach Barton initially took back in 2000, when he realized he could create a cool product – and solve a problem he often encountered – by finding a way for mobile phones to identify songs playing over the radio.

As it turned out, seven companies were already developing technology that monitored radio stations and allowed consumers to call a number and find out what they’d just heard. It took thinking from first principles for Barton to move past the familiar and uncover the two basic truths that would become Shazam: that music is audible, and that mobile phones have microphones.

“The breakthrough idea for Shazam was not, ‘What's that song?’” he said. “The breakthrough idea was, ‘What if you could identify the song from sound in thin air?’ That was something no one was doing.”

Achieving the Impossible

As Barton soon discovered, a great idea isn’t worth much without the means to execute it. As his nascent team met with the world’s top electrical engineers specializing in digital signal processing, they were told not only that the technology to identify songs didn’t exist, but that no one knew how to make it.

In short, the problem was that Shazam had to distinguish between music and background noise, then identify the music from a nonexistent dataset of literally every song ever recorded. When they finally brought in their technical co-founder, Avery Wang, the roadblock remained: even he, with four degrees from Stanford, thought it was impossible.

Because innovation requires a certain blasé attitude towards the impossible, Wang went on to develop Shazam’s core technology anyway: an audio fingerprint known as a spectrogram. After being rejected by more than 100 venture capital firms, Barton’s team struck up a connection with an investor passionate about music, who provided them with the funding to bring Shazam to life.

Even with their game-changing technology, they had to continually find creative solutions to seemingly insurmountable problems, such as the simple fact that music databases didn’t yet exist. This one took equal parts ingenuity and elbow grease: they convinced the U.K.'s top CD distributor that digital music was the future, offering to digitize its inventory for free. “Then we employed about thirty 18-year-olds who worked in three eight-hour shifts, 24 hours a day, putting CDs into computers and then typing the name of every song, every album, every artist into a database that we built from scratch to create Shazam,” Barton said.

Soon, they had their product: a number that anyone could call to access a system that would record 15 seconds of a song, hang up, and text back the title. In 2023, the notion sounds almost analog. Then again, that’s the natural endpoint of any innovative idea. After long enough, it’s just a normal part of everyday life.

Escaping the Prison of the Impossible

What can senior living providers learn from a music recognition app? Perhaps the most important takeaway is that transformative innovations are much more possible than they might seem – they just take a little creativity and a lot of dedication.

“We had to solve so many problems along the way,” Barton recalled. “How did we solve these problems? It wasn’t just having a great idea. It was creative persistence. Each problem, as we faced it – whether it was building the search engine or the music database or working with a basic phone – it was about solving each problem by thinking creatively.”

To break norms and build truly innovative products, he suggested, you have to think like a prisoner plotting to break free. “There’s not a known way to escape from prison; they have to sit there and think of all the possibilities and reinvent ideas until they can come up with a way of escaping,” he said. “That's how you solve all these difficult problems you encounter. You apply creative persistence.”

You also have to bring a level of obsessiveness that makes outside-the-box solutions a little easier to come by. At Shazam, that meant sending couriers to the BBC to borrow CDs of new releases, which at the time were delivered exclusively to radio stations before they were made available for public purchase. It also meant building relationships with Hollywood music supervisors, ensuring unknown tracks were already in the Shazam database by the time they premiered on TV.

“When you have an obsession like this, it costs a lot of money and takes a lot of time,” Barton said. “You're gonna have to stick with it if you want to see it through.”

Move Mountains to Eliminate Friction

One other lesson the senior living industry can learn from Shazam: the importance of simplicity. For all the complexity that went into building it – all the hurdles Barton’s team had to overcome – the basic idea isn’t complex at all. It’s an app that lets you identify any song, anywhere, just by holding up your phone. Easy as that.

This ability to eliminate friction is what defines successful ideas. Consider Dropbox, which seamlessly syncs files on your computer with their backups in the cloud; consider Tesla, whose cars unlock when you approach them. “You have to move mountains to eliminate friction,” Barton said. “Think through it end-to-end: what does your consumer have to experience? Then you have to just do everything you can, including inventing things, to eliminate any friction.”

He offered two paths for senior living providers looking to remove friction from their own products. There’s the obvious route, where you take something that already exists and design a simpler version. Then there’s the non-obvious route, where you invent something entirely groundbreaking. “That’s the harder part,” he said. “Far bigger risk, far bigger investment.” Inconveniently, it may also be the only way to create truly magical experiences.

Barton’s final piece of advice: find an emotional connection to the work. At Google, employees are encouraged to spend 20% of their time on personal projects, because these are often the ones that end up changing the world. (Ever heard of Gmail or AdSense?) In senior living, that connection already drives every aspect of the business. That means providers are already set up for success – they just need to start looking beyond the familiar and towards the transformative.

“Try this tomorrow: build from basic truths, question the assumptions, and start from zero,” Barton said. “Build not a house, but a home.”

Posted by

SLIF heads to Carlsbad!

The One of a Kind Retreat for Senior Housing Leaders.

May 31 - June 2, 2026 | Carlsbad, CA

Learn More

Comments